Today’s Tania Talks Museums With post veers into new territory. I was scheduled to talk about museums with Audrey Flack when I was in New York City in mid-May. Unfortunately her husband died days before our meeting, and we did not get together. I wanted to give her a little time before I rescheduled via zoom, but I waited too long. She passed away on June 28, less than a month after her 93rd birthday. While processing her death, I went back to her books. I decided to share a few of her quotes about museums here. I pulled them from her recently published memoir With Darkness Came Stars (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024), Art & Soul: Notes on Creating (Penguin, 1986), and On Painting (Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 1984).

The truth is I talked about museums with Audrey every time we spoke. I don’t know another person who loved museums more than she did. She would often visit a particular painting or sculpture at the Met or another museum and leave after that one viewing. She befriended art and artists, both living and long gone.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Hispanic Museum were second homes for me. I wandered their halls looking for answers, solace, and understanding, and there was always someone who spoke to me: Giotto; Mantegna; Antonello da Messina with his beautiful soulful self-portrait; Carlo Crivelli, long a favorite of mine—I studied the expressions in his canvases—grimacing, frowning, always intense; Rembrandt’s self-portraits; Tintoretto; Rubens. Later, Mary Cassatt, Kaethe Kollwitz, Cézanne, Pollock, Kline, Luisa Roldán, Martinez Montañés, Rachel Ruysch, Peter Claesz, Willem Claesz Heda, Jan Davidsz de Heem, the pre-Raphaelites, Bouguereau—all message givers. -On Painting, 28

Audrey admired individual brush strokes, dabs of color, compositions, structures, and frames, and made references to those elements in conversation. Talking with Audrey took you places you never went with others. I regret not talking with her more.

I was insistent about the color of those grapes [in Wheel of Fortune], though it was difficult to achieve the strange orange shade I wanted. A year later in the National Gallery in Washington, while viewing an Edvard Munch exhibition, I stopped sharply in front of a painting which held that exact color. The picture was called The Smell of Death. Munch had sought the same shade, and for the same associative powers. -On Painting, 90

I met Audrey in 1996. My former art history professor Art Jones introduced us. I invited Audrey to speak during the run of Exposed! Telfair Women Artists and Patrons, an exhibition I co-curated with former colleague Colleen Rice at the Telfair Academy in Savannah, Georgia.

Audrey had never been to Savannah, so I toured her around the city for a few of the 24 hours she was in town. Our tour included her first visit to a Walmart (she was curious), and a stop at my favorite live oak tree. I thought she might find the tree of interest because she was a sculptor. My instincts were correct. She oooohed and aaaahed as we approached the tree by car, and fell silent as she slowly walked up to the majestic oak. She placed her hands gently on the long limbs that touched the ground. Her soft, precise movements made her appear as if she were checking the tree’s pulse. Finally she hugged the tree. I witnessed her deep connection. The moment felt profound.

I recalled that encounter when I read the following passage in her book On Painting. The description of her experience with the Madonna sculpture by 17th-century artist Luisa Roldán in Seville, Spain, mimicked what I imagined she felt when she met the live oak.

The Macarena was standing there in all her glory, magnificent and serene. This masterpiece sent out vibrations which produced in me an electric sensation like one I had experienced when I stood in front of a Botticelli tondo at the Morgan Library in New York. -On Painting, 32

Years later I met Audrey for a short visit at the New York Historical Society. As we caught up she told me she was trying to find a home for a 12-foot plaster maquette of her Queen Catherine sculpture. She asked if the Telfair would be interested. She proposed loaning the sculpture, and then later converting the work to a gift if all parties agreed. I loved the idea. I immediately pictured Queen Catherine in the middle of the Telfair Academy’s sculpture gallery in the original location of the plaster cast of the Farnese Bull, which had been destroyed in the mid-20th century. My colleagues disagreed. The sculpture now resides at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio.

I have other Audrey stories, but I’ll end this post with her words. If you would like to know about Audrey and her work, do read a few of her many obituaries. I especially enjoyed reading those written for ARTnews, Smithsonian Magazine, and The Art Newspaper.

Jolie Madame was exhibited at the New York Cultural Center [at Columbus Circle, now Museum of Arts and Design] in an exhibition called Women Choose Women. It was 1973 and the show was historic, the first time a large group of women were exhibited in a museum. The artists May Stevens and Sylvia Sleigh were forces in the women’s movement and wanted a woman to hang the show. They nominated me, a vote was taken, and I was unanimously elected. -WDCS, 194

It was my responsibility to determine where each painting would hang and where sculpture would be placed. I wanted the show to look strong but soon realized that all of the works were small. Dwarfed by the scale of the museum, they looked inconsequential. Mario Amaya, the director of the museum, had set a size limit; there were to be no large works. It was clear to me that this women’s show would be dismissed as “petite ladies’ work” if those restrictions were held to. I met with Amaya the next morning and voiced my concerns. It took a lot of convincing, but he agreed that larger works could be hung, and I literally ran out of the room to telephone as many of the artists as I could get hold of—Alice Neel, Joan Mitchell, Perle Fine, Betty Parsons, and many others. -WDCS, 196

The history of Western art is basically Christian. That is what I knew and grew up with. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is filled with paintings of the Crucifixion. Crosses jump off the walls of museums all over the world. Had I ever seen a Star of David in a museum? No, not even one! The only painting with Jewish content I could think of was Marc Chagall’s rabbi wearing a Jewish prayer shawl. It seems I was puncturing a hole in the silent but powerful and exclusive tradition of Western art. I continued working on World War II for well over a year. The last brushstroke was painted in May 1978. It was one of the first paintings on the subject to reach the public. -WDCS, 212

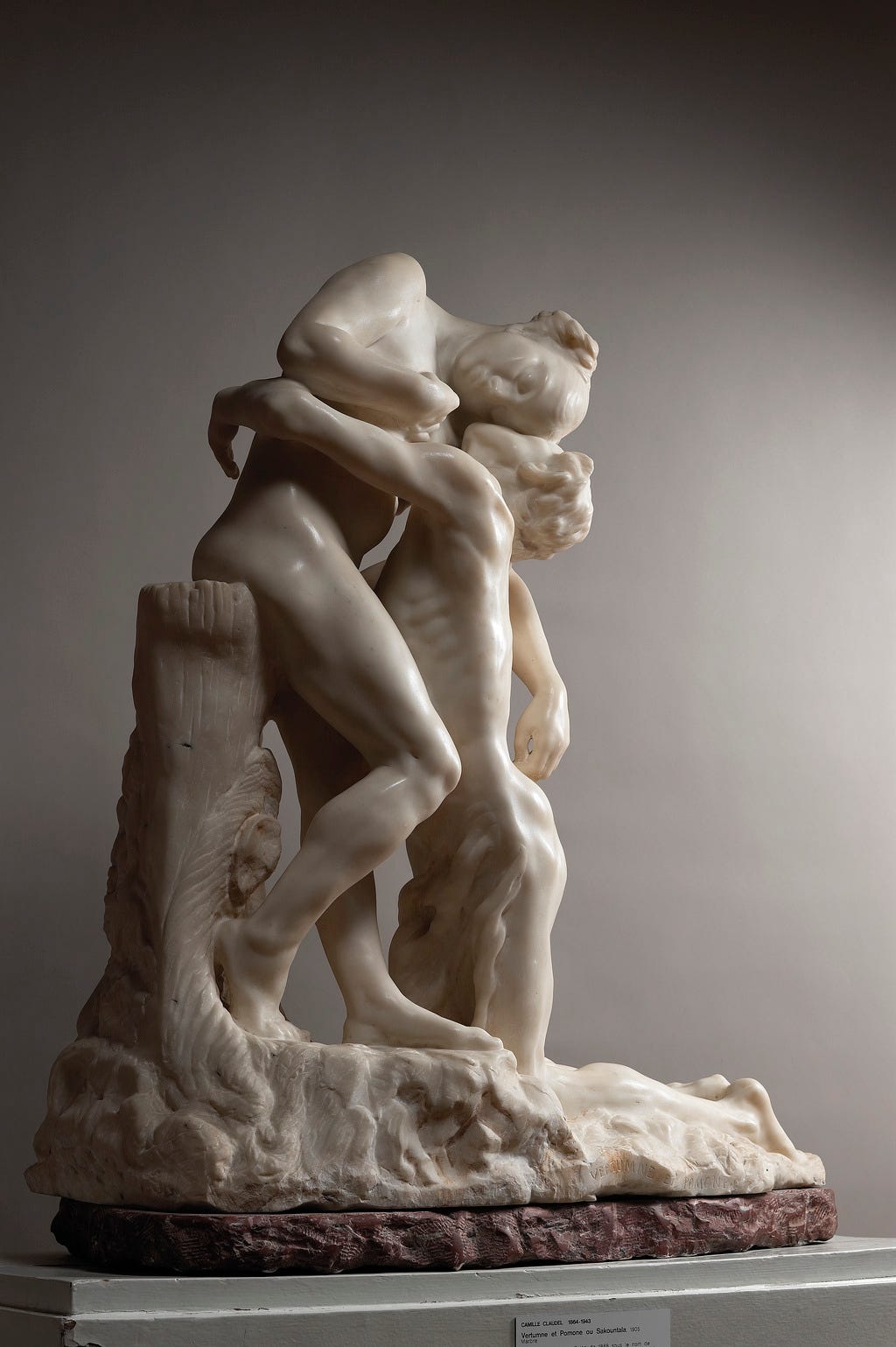

We arrived in Paris on May 15. This was a time for art—looking, visiting museums, and sketching. I saw a poster announcing an exhibition of Camille Claudel at the Musée Rodin. I had never felt drawn to visit the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia, though I passed it frequently. Rodin is an artist I kept at a certain distance, although I never knew why, and I always felt slightly guilty about it . . . Upon entering a hall of the Musée Rodin, I was surprised to come upon some sculpture that was new to me, superficially Rodin-like, yet possessing a totally different energy. I began to respond empathetically; I liked the work. I became excited by the forms, the images, the weight and balance of the figures against each other . . . I had discovered a new artist! Why wasn’t he known? I liked him better than Rodin. We bought a catalog as we left the gallery, and my husband said to me, “from what I see in the catalog, Camille Claudel appears to be a woman.” Indeed she was. -Art & Soul, 73-74

I walked rapidly to the East Wing of the National Gallery to see the “Sculpture of India” show. I have exactly one hour until the museum closes. I run up the stairs, into the elevator. I want up—the tower; it goes down. Pressured for time, overworked, overstimulated, I finally enter the exhibition space and am met with calm and serene buddhas, goddesses, and bodhisattvas, bestowing grace and wisdom. For the first time in a week, the tension drains from my body and I am at peace in front of these ancient statues. What a blessing. I silently thank all of those ancient sculptors and stonecarvers for the years of loving and caring—every jewel, every bead precisely chiseled and sanded. Thank you. -Art & Soul, 141

This is how I like to think of Audrey now, with the “calm and serene buddhas, goddesses, and bodhisattvas, bestowing grace and wisdom.” Rest in peace Audrey Flack.

I had no idea you had a relationship with Audrey Flack - what a privilege!

So sad that she died so soon after her husband.