Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina is the sort of exhibition one walks away from thinking about later. It’s my favorite kind of exhibition—small and focused; thought-provoking; lots of context; filled with aesthetically beautiful and profoundly powerful objects; and featuring a subject of which I have some knowledge and interest. Hear Me Now centers around the work of the once-enslaved potter Dave or David Drake, and the countless named and unnamed, enslaved men, women, and children who ran the pottery industry in and around Edgefield, South Carolina, prior to the end of the Civil War.

Hear Me Now is on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta until May 12, 2024. The exhibition is the fourth stop on a four-city tour, following the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor. The first three venues each had a curatorial connection to the exhibition. Here are the curators talking about their work at the Met, the exhibition’s opening museum:

The core of the exhibition features earth-toned clay storage jugs, pots, pitchers, and other objects used to house and serve food. Other objects made by enslaved people and their descendants, including furniture, quilts, and a basket, as well as discarded pottery shards retrieved from trash pits, and maps and interpretive text help contextualize the presentation.

A pre-colonial earthenware bowl made by a Native American and contemporary ceramics made by present-day artists who are inspired by the historical creations featured in Hear Me Now demonstrate a web of continuity in craft and spirit. Together the exhibition says: “we are all connected through time and place and material.”

All the objects in this exhibition pulse with life, but one piece in particular stopped me in my tracks—the bottom of a broken pot with a human’s hand smeared in the glaze and/or clay.

The label notes “Possibly Dave” as the maker. I presume the curators speculated he made this piece because of the size of the pot, as indicated by the width of the fragmented base. Dave/David Drake was known for making very large storage jugs. He was also known to have worked at Stony Bluff Manufactory from about 1848 to 1867, the location of the found pottery shard.

There is no way to know for sure the name of the person whose handprint was captured on this clay vessel, but we can acknowledge the person was almost certainly enslaved. Many enslaved people were involved in the making and moving of the large volume of manufactured goods at the Stony Bluff site, and other similar industrial facilities.

While we do not know the name of the person who handled this pottery, we know they existed. We see their palm lines. They say: “I was here.”

This palmprint entranced me, and my imagination ran wild when I saw this fragment. A seemingly quick movement that created the smudge on this discarded piece of pottery made in the 19th century has become a conduit to the 21st century.

I had to resist the impulse to put my hand on the vitrine cover opposite the handprint. Apparently I was not the only person to feel this urge. I found this image of a child reaching out to the unknown 19th century person on Instagram. This image was taken at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

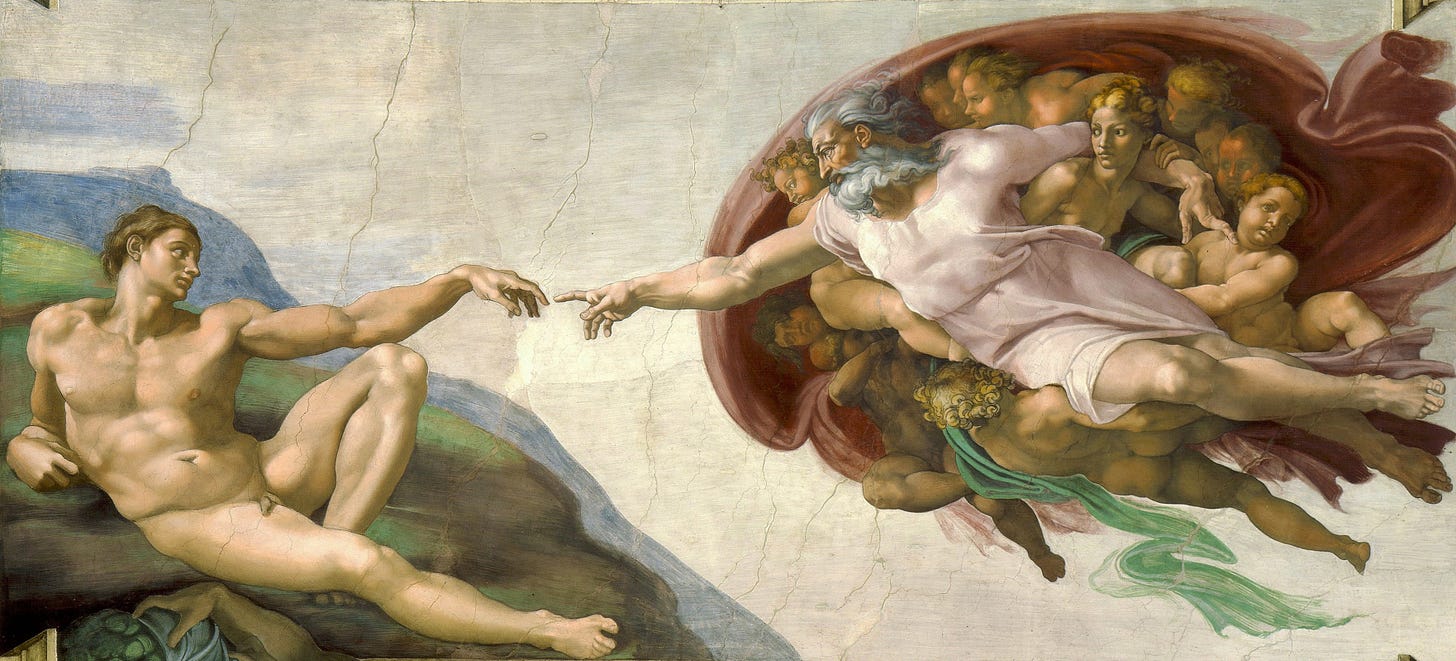

The connection between then and now exists through a space/time continuum. Someone nearly two centuries ago pushed their hand against a metaphorical membrane. I thought about seeing a baby’s hand or foot pressed against a belly during pregnancy, and imagined a person placing their hand on a glass wall, not unlike an incarcerated person simulating touch with a visitor. More personally, I recalled the barrier I experienced when I was hospitalized as a child, zipped up in an oxygen tent. My memories are vague, but I recall how the opaque partition blurred my vision of others on the outside of the shield, and how I reached out to touch someone’s hand with the thin-skinned plastic between us. I also thought about Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam at the Sistine Chapel.

Kate Hoernle (my editor) reminded me of another reference: “the universal symbol of hands as seen in petroglyphs and pictograms from cultures throughout the world, as in the caves in Lascaux, Native cliff dwellings, and ancient sites in Africa and Australia.”

The ideas and visions conjured up by the handprint and the rest of the work in this exhibition capture the essence of the human need for connection and expression. In a way, Hear Me Now has pierced the veil, bridging us to our past.

thank you for including your reactions and associated memories in addition to descriptions of the artifacts