Some of my most memorable museum experiences happen when wandering through a site on a first visit. In 2013, I had such an experience when I stumbled across the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants at the Harvard Museum of Natural History in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Destined for the Museum of Natural History on a pleasant summer day, my husband, two young daughters, and I set out on a nearly 4-mile urban hike from the Boston Public Library. We meandered along Marlborough Street in Boston’s Back Bay, crossed the Charles River, and walked through the campuses of MIT and Harvard.

Once at the museum we spent most of our time in the Great Mammal Hall. My girls were enthralled by the large taxidermy display and skeletons packed into the poorly lit room that felt old, dusty and antiquated. They didn’t seem to notice, and though I did, I loved it. The presentation served as a snapshot of earlier museum methodologies, which focused on amassing collections of all sorts. Often the goal was quantity rather than study and understanding.

After our time with the great mammals, we visited the minerals and gemstones. As we were leaving the museum, almost as an afterthought, I suggested we walk through the Glass Flowers exhibit. I noticed the collection as we entered the Earth and Planetary Sciences gallery and was intrigued. My family was not as enthusiastic. Our 2-plus-hour visit had pushed their limits. They were tired and hungry. “Just for a few more minutes,” I pleaded and darted into the gallery. They moaned and drooped their shoulders but followed me.

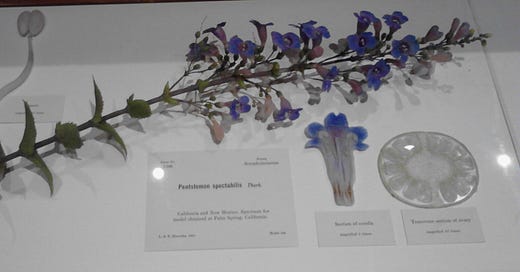

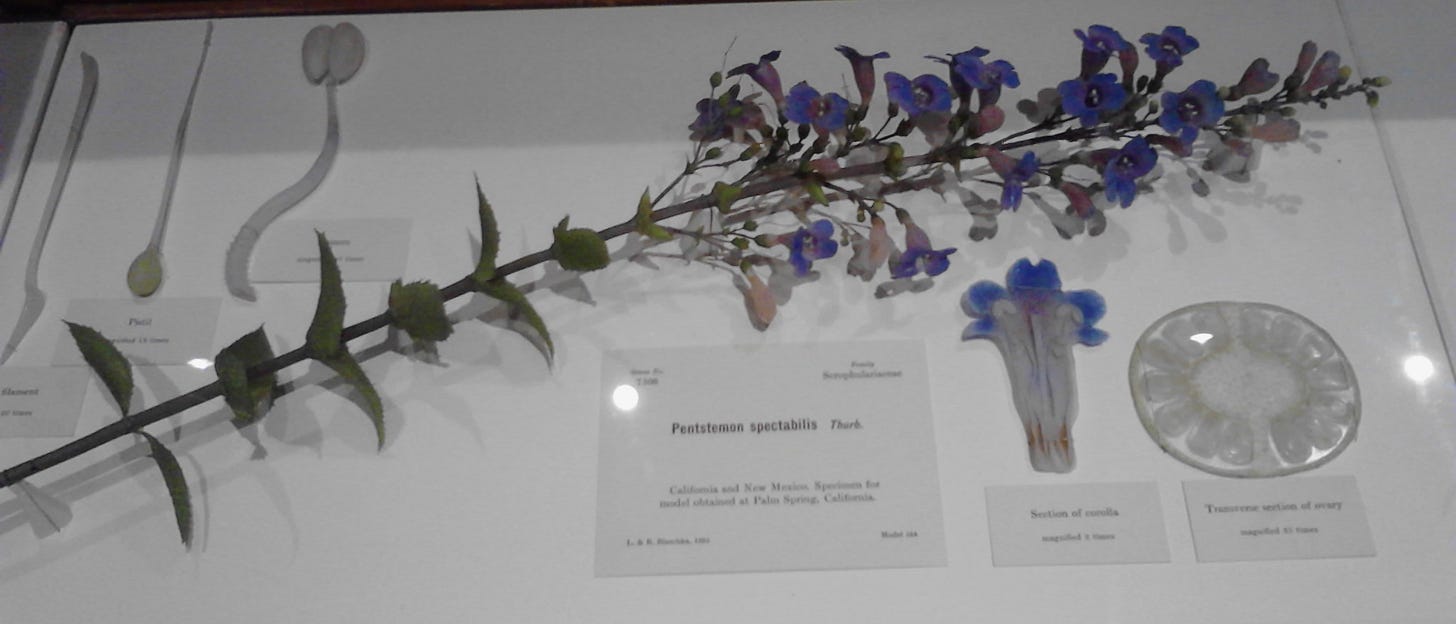

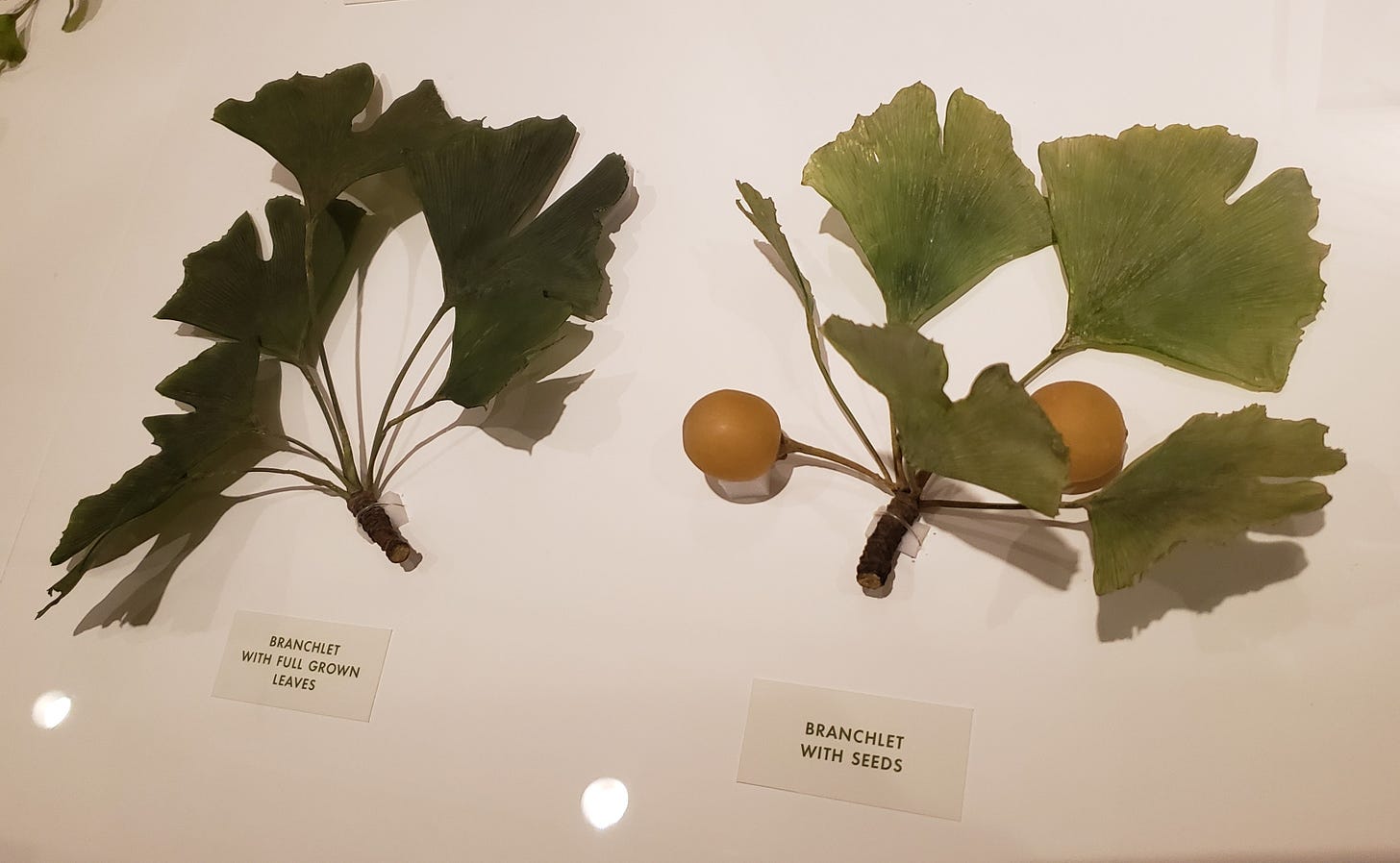

I was mesmerized. I lamented that we didn’t begin our tour in this gallery. The glass models of flowers and plants were realistic and beautiful and, I learned, scientifically accurate. I wanted to open the old cases and touch them. Like in the Great Mammal Hall, this collection appeared dusty and dated, but glorious. As I slowly moved from case to case, my family zipped through the room.

My attempts at coaxing them to look carefully were met with their own pleas, “Mom, pleeeaaase, let’s go.” They were zapped. Quickly I scanned the room and exited. I knew I would be back.

I returned in 2023. This time I was alone in the gallery. I spent at least a couple of hours studying the collection, and learning about the makers—a father, son duo, originally from Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic), and their work—more than 4,300 models representing 780 plant species. Their work spanned five decades from 1886-1936.

Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka’s glassmaking skills had developed within their family over generations, dating back to the 15th century. They specialized in jewelry making. They also made glass eyes and laboratory glassware. An interest in the natural world led them to create glass plants and marine invertebrates, first as a personal pursuit then later to share with the public. Harvard’s founding director of the Botanical Museum, George Lincoln Goodale, pursued and persuaded the artists to create models for his new museum. He funded the work through the financial support of his former student Mary Lee Ware and her mother Elizabeth C. Ware.

Before visiting the collection a second time, I learned the works had been conserved and reinstalled. I worried that the museum had removed the old cases, and that the old look and feel of the gallery would now feel modern and sterile. I was happily surprised to see I was wrong. Harvard’s exhibitions team did a fine job of conserving the glass models and old cases and reinstalling the gallery in a way that reflected updated scientific thinking, while also preserving the charming antique presentation.

To learn more about Harvard’s Glass Flowers, visit their website, which includes several videos about the collection and the conservation and reinstallation process: Glass Flowers: The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants | Harvard Museum of Natural History

Serendipity: I just saw this collection for the first time in May 2025 and was blown away!

What a marvelous find!